Jainism

Origins[edit]

Main article: Timeline of Jainism

The origins of Jainism are obscure.[2][6] During the 5th century BC, Vardhamana Mahāvīra became one of the most influential teachers of Jainism. Mahāvīra, however, was most probably not the founder of Jainism, which reveres him as the last of the great tīrthaṅkaras of this age and not the founder of the religion. He appears in the tradition as one who, from the beginning, had followed a religion established long ago.[7]

Pārśva, the traditional predecessor of Mahāvīra, is the first Jain figure for whom there is reasonable historical evidence.[8] He might have lived somewhere in the 9th–7th century BC.[9][10][11] Followers of Pārśva are mentioned in the canonical books; and a legend in theUttarādhyayana sūtra relates a meeting between a disciple of Pārśva and a disciple of Mahāvīra which brought about the union of the old branch of the Jain ideology and the new one.[7]

Literature[edit]

Main article: Jain literature

The tradition talks about a body of scriptures preached by all the tirthankaras of Jainism. These scriptures were contained in fourteen parts and were known as thepurvas. These were memorized and passed on through the ages, but were vulnerable and were lost because of famine that caused the death of several saints within a thousand years of Mahāvīra's death.[12]

The Jain Agamas are canonical texts of Jainism based on Mahāvīra's teachings. These comprise forty-six works: twelve angās, twelve upanga āgamas, six chedasūtras, four mūlasūtras, ten prakīrnaka sūtras and two cūlikasūtras.[13]

The Digambara sect of Jainism maintains that these agamas were also lost during the same famine. In the absence of authentic scriptures, Digambaras use about twenty-five scriptures written for their religious practice by great Acharyas. These include two main texts, four Pratham-Anuyog, three charn-anuyoga, four karan-anuyoga and twelve dravya-anuyoga.[14]

Jains developed a system of philosophy and ethics that had a great impact on Indian culture. They have contributed to the culture and language of the Indian states Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh. Jain scholars and poets authored Tamil classics of theSangam period, such as the Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi and Nālaṭiyār.[15] In the beginning of the mediaeval period, between the 9th and 13th centuries, Kannada language authors were predominantly of the Jain and Lingayatifaiths. Jains were the earliest known cultivators of Kannada literature, which they dominated until the 12th century. Jains wrote about the tirthankara and other aspects of the faith. Adikavi Pampa is one of the greatest Kannada poets. Court poet to the Chalukya king Arikesari, a Rashtrakuta feudatory, he is best known for hisVikramarjuna Vijaya.[16]

Jains encourage their monks to do research and obtain higher education. Monks and nuns, particularly inRajasthan, have published numerous research monographs. This is unique among Indian religious groups. The 2001 census states that Jains are India's most literate community.[4] Jain libraries, including those atPatan and Jaisalmer, have a large number of well preserved manuscripts.[5][17]

Doctrine[edit]

The nature of truth[edit]

Main article: Anekantavada

One of the most important and fundamental doctrines of Jainism isanēkāntavāda. It refers to the principles of pluralism and multiplicity of viewpoints, and to the notion that truth and reality are perceived differently from diverse points of view, no single one of which is complete.[18][19]

Jains contrast all attempts to proclaim absolute truth with this theory, which can be illustrated through the parable of the blind men and an elephant. In this story, each blind man feels a different part of an elephant: its trunk, leg, ear, and so on. All of them claim to understand and explain the true appearance of the elephant but, due to their limited perspectives, can only partly succeed.[20] This principle is more formally stated by observing that objects are infinite in their qualities and modes of existence, so they cannot be completely grasped in all aspects and manifestations by finite human perception. Only Kevalins—omniscient beings—can comprehend objects in all aspects and manifestations; others are only capable of partial knowledge.[21] Accordingly, no single, specific, human view can claim to represent absolute truth.[18]

Anekāntavāda encourages its adherents to consider the views and beliefs of their rivals and opposing parties. Proponents of anekāntavāda apply this principle to religions and philosophies, reminding themselves that any of these—even Jainism—that clings too dogmatically to its own tenets is committing an error based on its limited point of view.[22] The principle of anekāntavāda also influenced Mohandas Gandhi to adopt principles of religious tolerance, ahiṃsā and satyagraha.[23]

Syādvāda is the theory of conditioned predication, which recommends the expression of anekānta by prefixing the epithet Syād to every phrase or expression.[24] Syādvāda is not only an extension of anekānta intoontology, but a separate system of logic capable of standing on its own. The Sanskrit etymological root of the term syād is "perhaps" or "maybe", but in the context of syādvāda it means "in some ways" or "from some perspective". As reality is complex, no single proposition can express its nature fully. The term syāt- should therefore be prefixed to each proposition, giving it a conditional point of view and thus removing dogmatism from the statement.[25] Since it comprises seven different conditional and relative viewpoints or propositions, syādvāda is known as saptibhaṅgīnāya or the theory of seven conditioned predications. These seven propositions, also known as saptibhaṅgī, are:[26]

- syād-asti—in some ways, it is;

- syād-nāsti—in some ways, it is not;

- syād-asti-nāsti—in some ways, it is, and it is not;

- syād-asti-avaktavyaḥ—in some ways, it is, and it is indescribable;

- syād-nāsti-avaktavyaḥ—in some ways, it is not, and it is indescribable;

- syād-asti-nāsti-avaktavyaḥ—in some ways, it is, it is not, and it is indescribable;

- syād-avaktavyaḥ—in some ways, it is indescribable.

Each of these seven propositions examines the complex and multifaceted nature of reality from a relative point of view of time, space, substance and mode.[26] To ignore the complexity of reality is to commit the fallacy of dogmatism.[19]

Nayavāda is the theory of partial standpoints or viewpoints.[27] Nayavāda is a compound of two Sanskritwords: naya ("partial viewpoint") and vada ("school of thought or debate"). It is used to arrive at a certaininference from a point of view. Every object has infinite aspects, but when we describe one in practice, we speak only of relevant aspects and ignore the irrelevant.[27] This does not deny the other attributes, qualities, modes and other aspects; they are just irrelevant from a particular perspective. As a type of critical philosophy, nayavāda holds that philosophical disputes arise out of confusion of standpoints, and the standpoints we adopt are "the outcome of purposes that we may pursue"—although we may not realise it. While operating within the limits of language and perceiving the complex nature of reality, Māhavīra used the language of nayas. Naya, being a partial expression of truth, enables us to comprehend reality part by part.[28]

Metaphysics[edit]

Main article: Jain metaphysics

Soul and karma[edit]

According to Jains, souls are intrinsically pure and possess the qualities of infinite knowledge, infinite perception, infinite bliss and infinite energy.[29] In contemporary experience, however, these qualities are found to be defiled and obstructed, on account of the soul's association with a substance called karma over an eternity of beginningless time.[30] This bondage of the soul is explained in the Jain texts by analogy with gold, which is always found mixed with impurities in its natural state. Similarly, the ideally pure state of the soul has always been overlaid with the impurities of karma. This analogy with gold further implies that the purification of the soul can be achieved if the proper methods of refining are applied.[30] Over the centuries, Jain monks have developed a large and sophisticated corpus of literature describing the nature of the soul, various aspects of the working of karma, and the means of attaining liberation.[30]

Tattva[edit]

Jain metaphysics is based on seven or nine fundamentals which are known as tattva, constituting an attempt to explain the nature of the human predicament and to provide solutions to it:[31]

- Jīva: The essence of living entities is called jiva, a substance which is different from the body that houses it. Consciousness, knowledge and perception are its fundamental attributes.

- Ajīva: Non-living entities that consist of matter, space and time fall into the category of ajiva.

- Asrava: The interaction between jīva and ajīva causes the influx of a karma (a particular form of ajiva) into the soul, to which it then adheres.

- Bandha: The karma masks the jiva and restricts it from having its true potential of perfect knowledge and perception.

- Saṃvara: Through right conduct, it is possible to stop the influx of additional karma.

- Nirjarā: By performing asceticism, it is possible to shred or burn up the existing karma.

- Mokṣa: The jiva which has removed its karma is said to be liberated and to have its pure, intrinsic quality of perfect knowledge in its true form.

Some authors add two additional categories: the meritorious and demeritorious acts related to karma. These are called puṇya and pāpa respectively. These fundamentals acts as the basis for the Jain metaphysics.

Cosmology[edit]

Main article: Jain cosmology

Jain beliefs postulate that the universe was never created, nor will it ever cease to exist. It is independent and self-sufficient, and does not require any superior power to govern it. Elaborate description of the shape and function of the physical and metaphysical universe, and its constituents, is provided in the canonical Jain texts, in commentaries and in the writings of the Jain philosopher-monks. The early Jains contemplated the nature of the earth and universe and developed detailed hypotheses concerning various aspects of astronomy and cosmology.[32]

According to the Jain texts, the universe is divided into three parts, the upper, middle, and lower worlds, called respectively urdhva loka, madhya loka, andadho loka.[33] It is made up of six constituents:[34] Jīva, the living entity; Pudgala, matter; Dharma tattva, the substance responsible for motion; Adharma tattva, the substance responsible for rest; Akāśa, space; and Kāla, time.[34]

Time is beginningless and eternal; the cosmic wheel of time, called kālachakra, rotates ceaselessly. It is divided into halves, called utsarpiṇī and avasarpiṇī.[35] Utsarpiṇī is a period of progressive prosperity, where happiness increases, while avasarpiṇī is a period of increasing sorrow and immorality.[36]

Jainism views animals and life itself in an utterly different light, reflecting an indigenous Asian understanding that yields a different definition of the soul, the human person, the structure of the cosmos, and ethics.[37]

Universal history[edit]

According to Jain legends, sixty-three illustrious beings called Salakapurusas have appeared on earth.[38] The Jain universal history is a compilation of the deeds of these illustrious persons.[39] They comprise twenty-four tīrthaṅkaras, twelve cakravartins, nine baladevas, nine vāsudevas and nine prativāsudevas.[38]

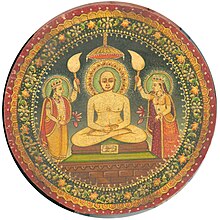

Tīrthaṅkaras are the human beings who help others to achieve liberation. They propagate and revitalize Jain faith and become role-models for those seeking spiritual guidance. They reorganize the fourfold order that consists of monks, nuns, laymen and laywomen.[40] Jain tradition identifies Rishabha (also known as Adinath) as the first tirthankara. The last two tirthankara, Pārśva and Mahāvīra, are historical figures whose existence is recorded.[41]

A cakravartin is an emperor of the world and lord of the material realm.[38] Though he possesses worldly power, he often finds his ambitions dwarfed by the vastness of the cosmos. Jain puranas give a list of twelve cakravartins. They are golden in complexion.[42] One of the greatest cakravartin mentioned in Jain scriptures is Bharata. Traditions say that India came to be known as Bharatavarsha in his memory.[43]

There are nine sets of baladeva, vāsudeva and prativāsudeva. Certain Digambara texts refer to them as balabhadra, narayana and pratinarayana, respectively. The origin of this list of brothers can be traced to theJinacaritra by Bhadrabahu (c. 3rd–4th century BCE).[44] Baladeva are non-violent heroes, vasudeva are violent heroes and prativāsudeva can be described as villains. According to the legends, the vasudeva ultimately kill the prativasudeva. Of the nine baladeva, eight attain liberation and the last goes to heaven. The vasudeva go to hell on account of their violent exploits, even if these were intended to uphold righteousness.[45]

Ethics[edit]

Ahimsa[edit]

Main articles: Ahimsa in Jainism and Jain vegetarianism

The principle of nonviolence or ahimsa is the most distinctive and well known aspect of Jain religious practice. The Jain understanding and implementation of ahimsa is more radical, scrupulous, and comprehensive than in other religions.[46] Non-violence is seen as the most essential religious duty for everyone.[47]

A scrupulous and thorough application of nonviolence to everyday activities, and especially to food, is the most significant hallmark of Jain identity.[48] The Jain diet, observed by the followers of Jain culture and philosophy, is one of the most rigorous forms of spiritually motivated diet found either on the Indian subcontinent or elsewhere. It is completely vegetarian, excludes onions and garlic, and may additionally exclude potatoes and other root vegetables. The strictest forms of Jain diet are practised by the ascetics.[49]For Jains, lacto-vegetarianism represents the minimal obligation: food which contains even small particles of the bodies of dead animals or eggs is absolutely unacceptable. Jain scholars and activists support veganism, as the production of dairy products involves violence against cows. Strict Jains do not eat root vegetables, such as potatoes and onions, because tiny organisms are injured when the plant is pulled up, and also because a bulb or tuber's ability to sprout is seen as characteristic of a living being.[50]

Jains make considerable efforts in everyday life not to injure plants any more than necessary. Although they admit that plants must be destroyed for the sake of food, they accept such violence only inasmuch as it is indispensable for human survival, and there are special instructions for minimizing violence against plants. Jains also go out of their way not to hurt even small insects and other minuscule animals. They rarely go out at night, when it is more likely that they might trample insects. In their view, injury caused by carelessness is like injury caused by deliberate action.[51] Eating honey is strictly outlawed, as it would amount to violence against the bees. Jains avoid farming because it inevitably entails unintentional killing or injuring of small animals, such as worms and insects, but agriculture is not forbidden in general and Jain farmers exist.[52]Additionally, because they consider harsh words to be a form of violence, they often keep a cloth for a ritual mouth-covering, serving as a reminder not to allow violence in their speech.[53]

Although every life-form is said to deserve protection from injury, Jains admit that this ideal cannot be completely implemented in practice. Hence they recognise a hierarchy of life that gives less protection to immobile beings than to mobile ones, which are further distinguished by the number of senses they possess, from one to five. A single-sensed animal has touch as its only sensory modality. The more senses a being has, the more care Jains take for its protection. Among those with five senses, rational beings (humans) are the most strongly protected by ahimsa. Nonetheless, Jains agree that violence in self-defence can be justified,[54] and that a soldier who kills enemies in combat is performing a legitimate duty.[55] Jain communities have accepted the use of military power for their defence, and there have been Jain monarchs, military commanders, and soldiers.[56]

Self-control[edit]

Jainism encourages spiritual development through cultivation of personal wisdom and through reliance on self-control through vows.[57] Jains accept different levels of compliance for ascetics and lay followers.[57]Ascetics of this religion undertake five major vows:

- Ahimsa: Ahimsa means non-violence. The first major vow taken by ascetics is to cause no harm to living beings. It involves minimizing intentional and unintentional harm to other living creatures.

- Satya: Satya figuratively means truth. This vow is to always speak the truth. Given that non-violence has priority, other principles yield to it whenever they conflict: in a situation where speaking truth could lead to violence, silence is to be observed.[57]

- Asteya: The third vow, asteya, is to not take anything that is not willingly offered.[57] Attempting to extort material wealth from others or to exploit the weak is considered theft.

- Brahmacharya: The vow of brahmacharya requires the exercise of control over the senses by refraining from indulgence in sexual activity.

- Aparigraha: Aparigraha means non-possessiveness. This vow is to observe detachment from people, places and material things.[57] Ascetics completely renounce property and social relations.

Laymen are encouraged to observe the five cardinal principles of non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing,celibacy, and non-possessiveness within their current practical limitations, while monks and nuns are obligated to practise them very strictly.[57]

History[edit]

Main article: History of Jainism

Royal patronage[edit]

The ancient city Pithunda, capital of Kalinga, is described in the Jain text Uttaradhyana Sutra as an important centre at the time of Mahāvīra, and was frequented by merchants from Champa.[58]Rishabha, the first tirthankara, was revered and worshiped in Pithunda and is known as the Kalinga Jina. Mahapadma Nanda (c. 450–362 BCE) conquered Kalinga and took a statue of Rishabha from Pithunda to his capital in Magadha. Jainism is said to have flourished under Nanda empire.[59]

The Mauryan dynasty came to power after the downfall of Nanda empire. The first Mauryan emperor, Chandragupta (c. 322–298 BCE), became a Jain in the latter part of his life. He was a disciple of Badhrabahu, a jaina ācārya who was responsible for propagation of Jainism in south India.[60] The Mauryan king Ashoka was converted to Buddhism and his pro-Buddhist policy subjugated the Jains of Kalinga. Ashoka's grandson Samprati (c. 224–215 BCE), however, is said to have converted to Jainism by a Jain monk named Suhasti. He is known to have erected many Jain temples. He ruled a place calledUjjain.[61]

In the 1st century BCE the emperor Kharvela of Mahameghavahana dynasty conquered Magadha. He retrieved Rishabha's statue and installed it in Udaygiri, near his capital Shishupalgadh. Kharavela[62] was responsible for the propagation of Jainism across the Indian subcontinent. Hiuen Tsang (629–645 CE), a Chinese traveller, notes that there were numerous Jains present in Kalinga during his time.[63] The Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves near Bhubaneswar are the only surviving stone Jain monuments in Orissa.[64]

King Vanaraja (c. 720–780 CE) of cavada dynasty in northern Gujarat was raised by a Jain monk Silunga Suri. He supported Jainism during his rule. The king of kannauj Ama (c. 8th century CE) was converted to Jainism by Bappabhatti, a disciple of famous Jain monk Siddhasena Divakara.[65] Bappabhatti also converted Vakpati, the friend of Ama who authored a famous prakrit epic named Gaudavaho.[66]

Comments

Post a Comment